You only know when you try

I was listening to Ben Thompson and John Gruber discussing their VisionPro experience watching NBA games. They were frustrated. Apple keeps switching your perspective mid-game - you're sitting courtside, and suddenly you're teleported somewhere else. No choice. They just do it for you.

And my first thought was: couldn't Apple have figured this out before shipping? It feels so obvious. If I'm watching a football match from a specific seat in the stadium, I don't want to be yanked to a different spot without asking. Of course, that's annoying.

But then I caught myself. Was it actually obvious? Or does it only feel obvious now because someone experienced it?

This triggered something I've been wrestling with for years.

The Frustration I Kept Having With Myself

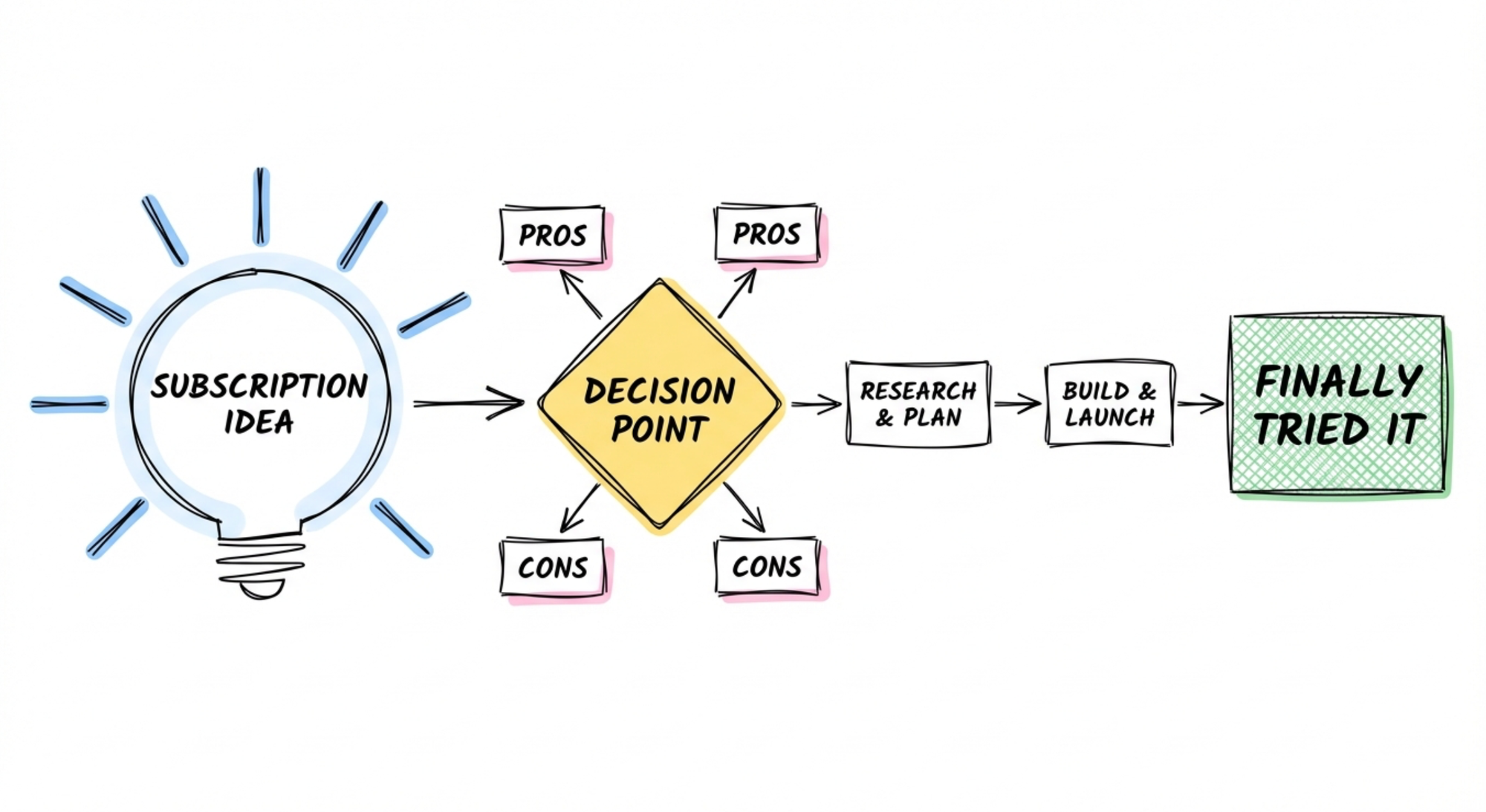

Last year, I finally tried a subscription model for my content. The idea had been bouncing around in my head for almost two years. Maybe I could turn my newsletter into a paid subscription. Maybe that's the right business model for what I'm building.

I talked to a lot of people about it. Everyone had opinions. Good idea because of this. Bad idea because of that. Classic pros and cons. I collected an extensive list. Once the AI models got good enough to brainstorm properly, I ran sessions with them too. Different angles, different scenarios, different considerations.

And then one of those AI sessions just said: "You only know when you try."

I hated that answer. Why do I always have to try things to know if they work?

Because this wasn't the first time. When I got started with YouTube, I had the same question spinning in my head. Would it be a good idea to do YouTube or not? I weighed the options. I thought about it. And then I just started - and only then did I actually find out what worked and what didn't.

Same with consulting projects. I'd think: maybe this type of project is a good fit for me. Looks interesting on paper. And then I'd start the project, and after a week I'd know immediately - no, this type doesn't work. But by then, I was committed. Stuck with it until I delivered what I promised.

Every time, the same pattern. I'd discover something that felt completely obvious in hindsight. And then I'd have these moments with myself. Not quite self-hate, but a softer version of it. This voice says: " You could have known before. Wasn't it obvious enough? Everything you discovered now was already on your list."

This kept happening. And I kept blaming myself for not seeing it earlier.

The Dimension That's Missing

And then, while listening to that podcast episode, something clicked.

When you plan things out, you can sketch scenarios. You can list what might happen. You can imagine how it could play out. But because it's not actually happening, something is missing. A dimension.

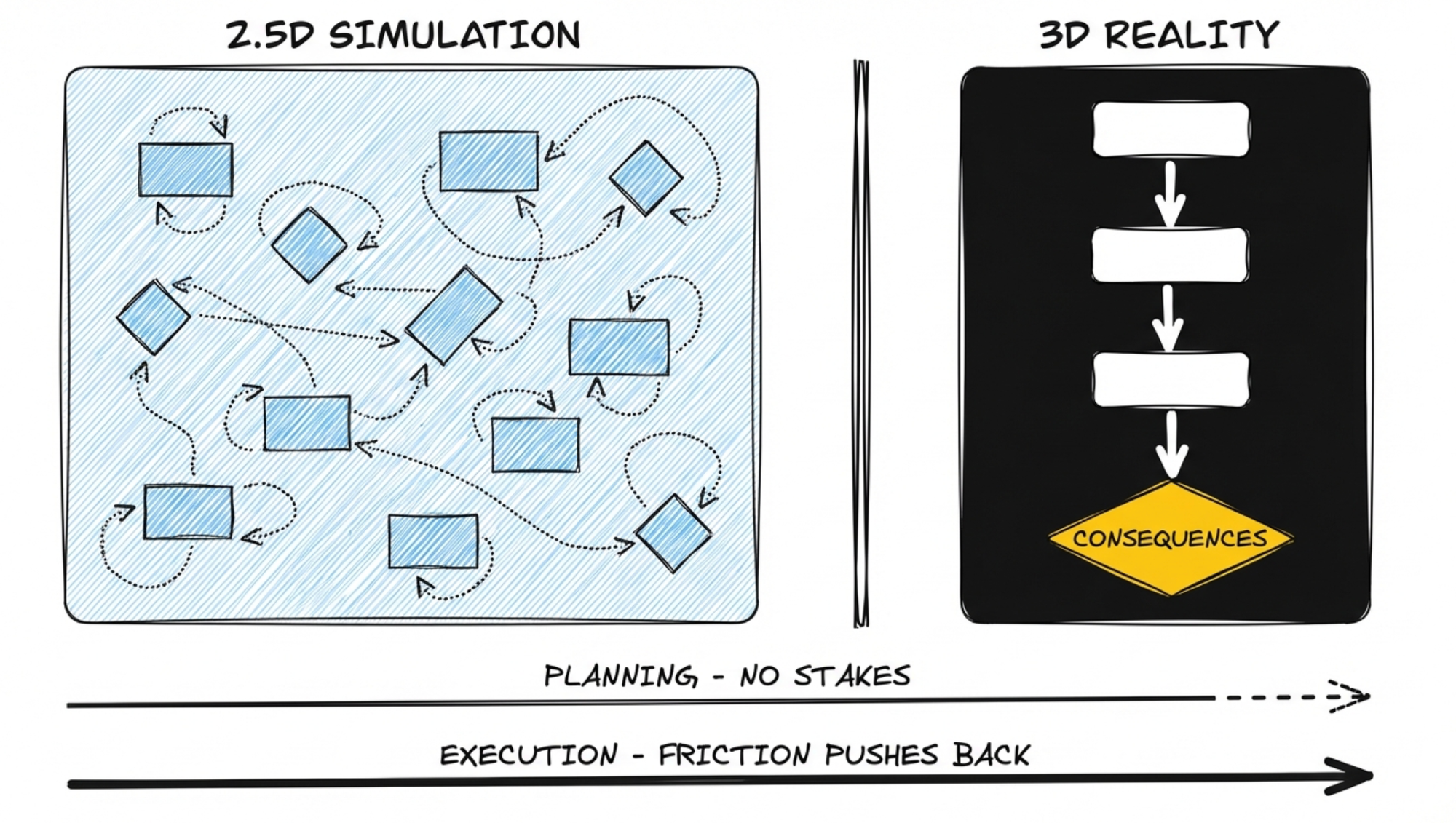

Think of it as 2D versus 3D. Planning is flat. You see the shape of something - the outline, the structure. But you don't see the depth. You can't. It's not a limitation of your list or your thinking. It's a limitation of the medium.

We need the lived experience to actually see. That's how we're built as humans.

When I realized this, I found a kind of peace I'd been looking for. It's not that I failed at planning. It's not that I should have been smarter or more thorough. The information on my list was never going to be enough - because information isn't experience. They're different dimensions.

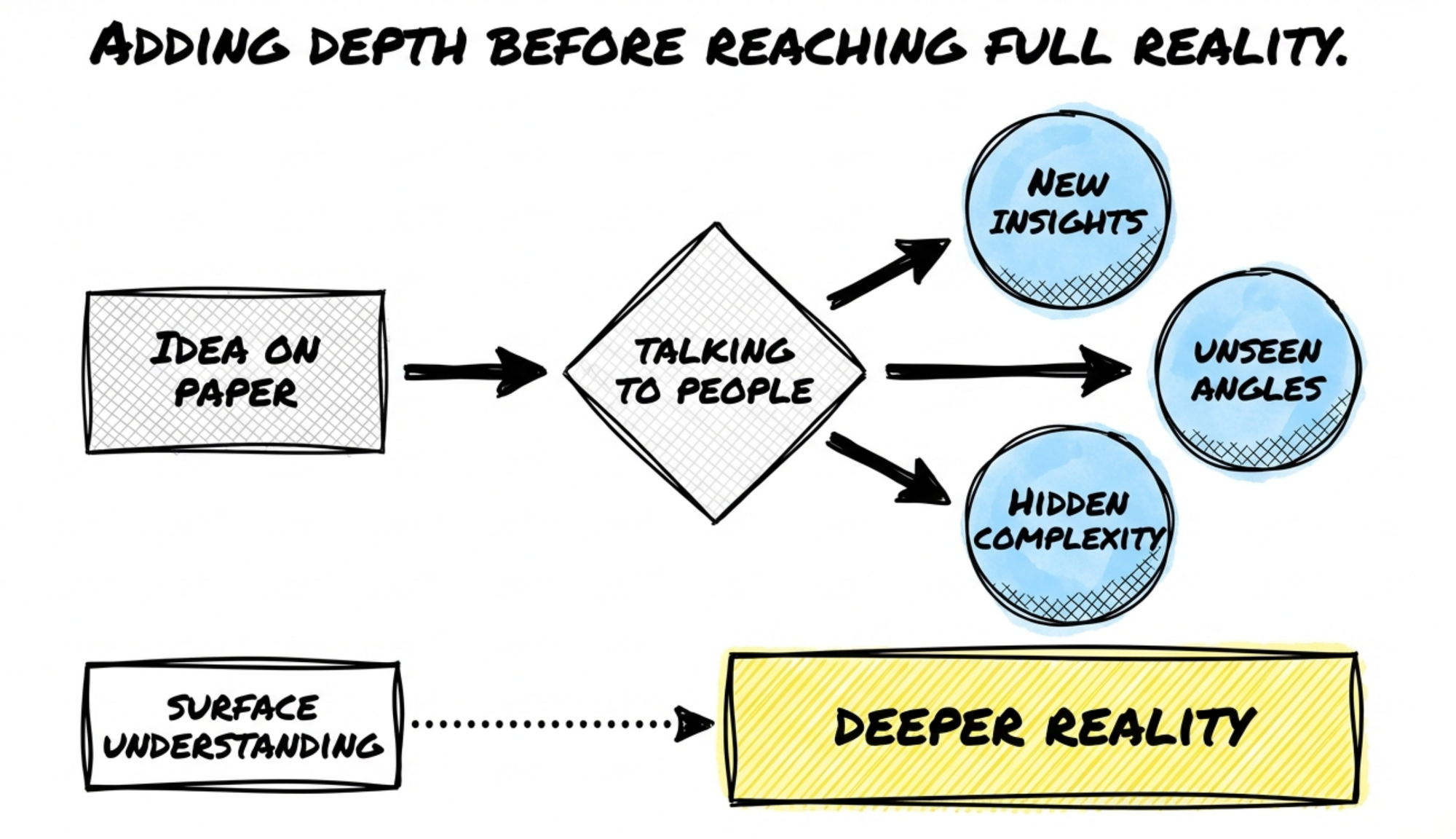

But here's what's interesting: the jump from 2D to 3D isn't binary. There are steps in between.

Talking and Writing: 2.5D

You start adding depth before you reach full reality.

I've been working on a new approach to data modeling - using jobs-to-be-done as a structuring principle instead of traditional layers. I had the idea sketched out. It made sense on paper.

Then I started talking to people about it. And something interesting happened. While I was explaining the approach - even before they said anything, even just seeing their face on the camera - I started to see things I hadn't seen before. I was articulating something, and in that moment of articulation, I added new layers. I started to refine specific parts. I noticed gaps.

The same thing happened when I wrote about it on LinkedIn. Some comments were what I expected - yes, makes sense, I agree. Not really adding depth. But there were one or two that hit differently. A perspective I didn't have. An angle I hadn't considered.

This is 2.5D. You're still not in full reality. You haven't tried it yet. But you're no longer flat either. The act of talking, explaining, writing - it forces you to rotate the idea. You see it from angles that pure thinking doesn't reach.

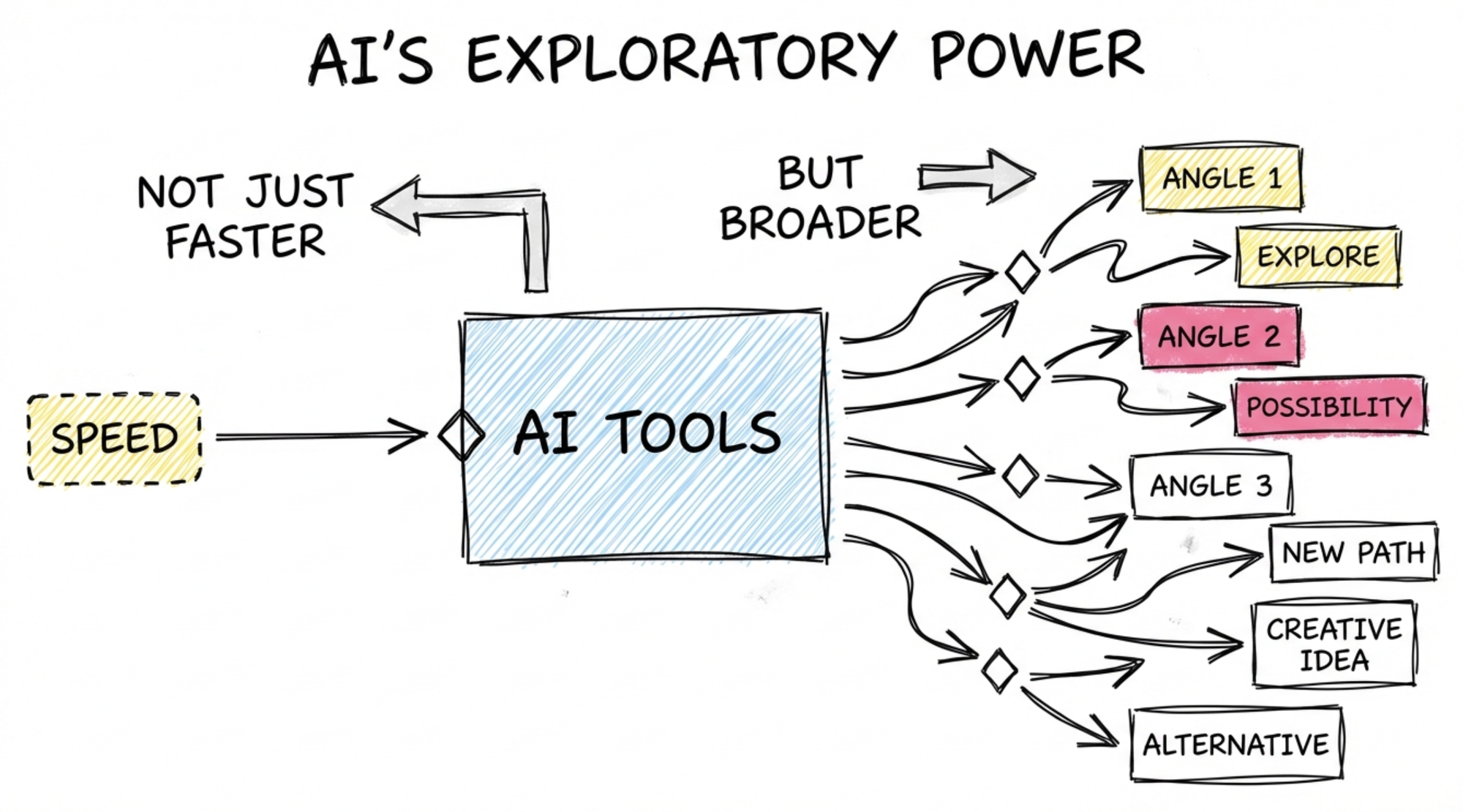

AI: Also 2.5D

When AI tools first became useful for daily work, everyone talked about speed. You can do things so much faster now. The model just writes it for you.

That never matched my experience. I wrote about this in my 2025 reflections - yes, on some measures, things got quicker. But that's not what actually changed. What changed is that things got broader.

AI lets me explore angles. Lots of them, quickly.

Take that jobs-to-be-done data modeling idea. I can take a model and say: here's a business, here are the metrics they care about, here's what we want to implement. Now here's my new approach. Let's play it out. What happens in the typical scenarios that occur when you work on a data stack for two years? Let's brainstorm how these could look with this approach.

And the model will run through scenarios. It'll find edges. It'll surface things I might not have thought about in that moment. This is valuable. This adds depth.

But is it 3D? No. It's still simulation.

I'm a big science fiction reader. And in almost every book with virtual reality, there's this moment where the simulation feels too flat somewhere. Something is off. The depth isn't quite right. That's what AI feels like to me right now - incredibly useful for rotating an idea, seeing it from many sides. But not the same as actually being in it.

What's In The Gap?

So what's actually in that space between 2.5D and 3D? What does reality provide that simulation can't?

I have no idea. But I think it's something about consequences. When you're planning, talking, writing, or even running scenarios with AI, nothing is at stake yet. You can rotate the idea endlessly. But you're not committed. There's no week two of a consulting project where you realize it's wrong and you still have to deliver.

Reality has friction. It pushes back. And apparently, we need that pushback to truly see.

The peace I found isn't that I can skip the trying. I can't. None of us can. The peace is that I can stop blaming myself for not knowing beforehand. The information was never going to be enough. It couldn't be.

So now the question changes. Not: how can I figure everything out before I start? But: how can I get to 3D faster? How can I try sooner, smaller, cheaper - so I learn what only reality can teach?

Maybe that's also where AI becomes most useful. Not to replace the trying. But to get through the 2D and 2.5D faster, so you have more time for what actually matters: the real thing.

Join the newsletter

Get bi-weekly insights on analytics, event data, and metric frameworks.